F*ck Disassemblers - A Deep Dive into Anti-Disassembly Techniques

F*ck Disassemblers - A Deep Dive into Anti-Disassembly Techniques

CX330🧛 [ 繁體中文 | English version ]

Preface

The advent of disassemblers has been a great blessing for reverse engineers, but not necessarily for malware authors and commercial software vendors. As a result, they have also started to study disassembler algorithms and explore how to attack or obfuscate these algorithms so that disassemblers can no longer function correctly. Such techniques are collectively referred to as anti-disassembly.

This article aims to explore the principles behind various anti-disassembly techniques and their corresponding countermeasures. Throughout this process, we will use two commercial disassemblers (and decompilers), Binary Ninja and IDA,[1] to observe the effectiveness of our anti-disassembly tricks.

How Disassemblers Work

The goal of a disassembler is to read machine code and convert it back into assembly language so that reverse engineers can better understand the code.

There are two relatively common disassembly algorithms: linear sweep and recursive descent. We will dive into these two different disassembly algorithms and discuss their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Linear Sweep

As the name suggests, the linear sweep algorithm linearly traverses all machine code bytes in an executable and converts them back into assembly language. Some relatively simple, lightweight, and basic disassemblers use this algorithm, such as objdump.

Let’s first look at a small piece of code to help us better understand how this algorithm works:

char buffer[BUF_SIZE];

int position = 0;

while (position < BUF_SIZE) {

x86_insn_t insn;

int size = x86_disasm(buf, BUF_SIZE, O, position, &insn);

if (size != 0) {

char disassembly_line[1024];

x86_format_insn(&insn, disassembly_line, 1024, intel_syntax);

printf("%s\n", disassembly_line);

position += size;

} else if {

/* invalid/unrecognized instruction */

position++;

}

}

x86_cleanup ();In this program, the x86_disasm function is repeatedly invoked to perform disassembly. The variable size is used to determine whether a valid instruction was disassembled. If no instruction is recognized, position is incremented by one; otherwise, position is increased by the size of the disassembled instruction. In short, we can see that the program uses a loop to linearly sweep through the entire machine code, which is why this approach is called “linear sweep.”

Because it only needs to scan through the machine code once to complete its job, its time complexity is , allowing it to finish relatively quickly. However, its drawbacks are equally obvious—most notably, it tends to disassemble too much code. For example, even if a control-flow instruction ensures that only one branch is ever executed, a linear sweep disassembler will still keep disassembling until it reaches the end of the section. A more fatal weakness is that it cannot distinguish between code and data. Although in the PE format the .text section is intended to store code, compilers often place some data into this section as well for efficiency or other reasons (a common example is pointers). As a result, the linear sweep algorithm cannot distinguish whether the bytes it sees are data or code, which leads to inaccurate disassembly.

For instance, consider a switch-case statement like the following code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i;

scanf("%d", &i);

switch (i) {

case 0: puts("case 0\n"); break;

case 1: puts("case 1\n"); break;

case 2: puts("case 2\n"); break;

case 3: puts("case 3\n"); break;

case 4: puts("case 4\n"); break;

case 5: puts("case 5\n"); break;

default: break;

}

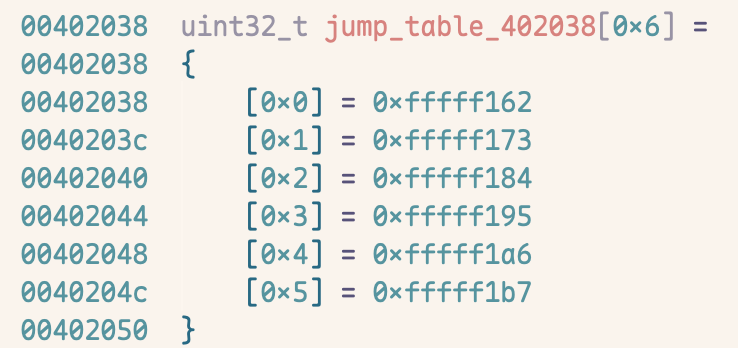

}The compiler may build a jump table data structure. Essentially, this structure is an array that stores pointers to the code corresponding to each case. Binary Ninja’s interpretation looks like the following:

At runtime, the program uses the switch value as an index into this table, retrieves the corresponding address, and jmps to it, which is faster than doing a sequence of comparisons.

If the compiler places this jump table in the code section, then a linear sweep disassembler will treat this chunk of data as code and interpret it as instructions, thereby producing incorrect assembly output. For this reason, we need another algorithm: recursive descent.

Recursive Descent

The recursive descent approach is also known as recursive traversal or flow-oriented disassembly. Its most significant difference from linear sweep is that during disassembly, it analyzes each instruction and tracks its control flow, building a worklist of addresses to be disassembled for each branch. The disassembler first follows one control-flow path and disassembles it; once it reaches the end of that path, it returns to the worklist to pick up another pending branch to continue disassembling.

For example, consider the following code:

test eax, eax

jz label_1

push failed_str

call printf

jmp label_2

failed_str: db 'Fail', 0

label_1:

xor eax, eax

label_2:

retnIn this example, the test instruction on the first line is followed by the conditional jump jz. When a recursive descent disassembler encounters jz, it will add label_1 to its worklist of addresses to be disassembled.

Since this is a conditional jump, the push on the third line can also be executed, so the disassembler will first process the disassembly of the third and fourth lines. Next, when it encounters the unconditional jump jmp, it will add label_2 to the worklist and ignore any code after jmp (because that code is skipped and never executed).

In the next step, it returns to the worklist and takes the first pending address—label_1—for disassembly, and then proceeds to process label_2. We can see that throughout this process, failed_str is never treated as code, so the resulting disassembly is more accurate. By contrast, a linear sweep disassembler would simply disassemble straight through to the end and treat that data as code.

Such conditional statements present the recursive descent disassembler with two branches to process: the true branch and the false branch. Disassemblers typically process the false branch first. This is because in real-world programs, the false branch often contains the “real” behavior. For example, we frequently see code such as:

if (error_condition) {

handle_error();

exit();

}

do_something();Compilers often translate this into assembly like:

test eax, eax

jz handle_error_label

; false branch

call do_something

jmp end_label

handle_error_label:

call handle_error

end_label:

retThis is why disassemblers are more inclined to trust the false branch—it is based on an assumption about typical compiler behavior.

However, recursive descent disassemblers also have drawbacks, namely higher time complexity. Because every branch must be processed, disassembly generally takes longer than with linear sweep.

Anti-Disassembly and Anti-Anti-Disassembly

Anti-disassembly techniques rely on carefully crafted bytes or code so that the disassembler is “fooled” into displaying code that differs from what actually executes. These techniques exploit the implicit assumptions and limitations of disassemblers. For example, a disassembler must assume that a given byte in the program can only belong to one instruction at a time. If we can trick the disassembler into decoding from an incorrect offset, we can mislead its interpretation and hide some legitimate instruction so that it is never shown.

Next, we will look at several anti-disassembly techniques.

Jump Instructions with the Same Target

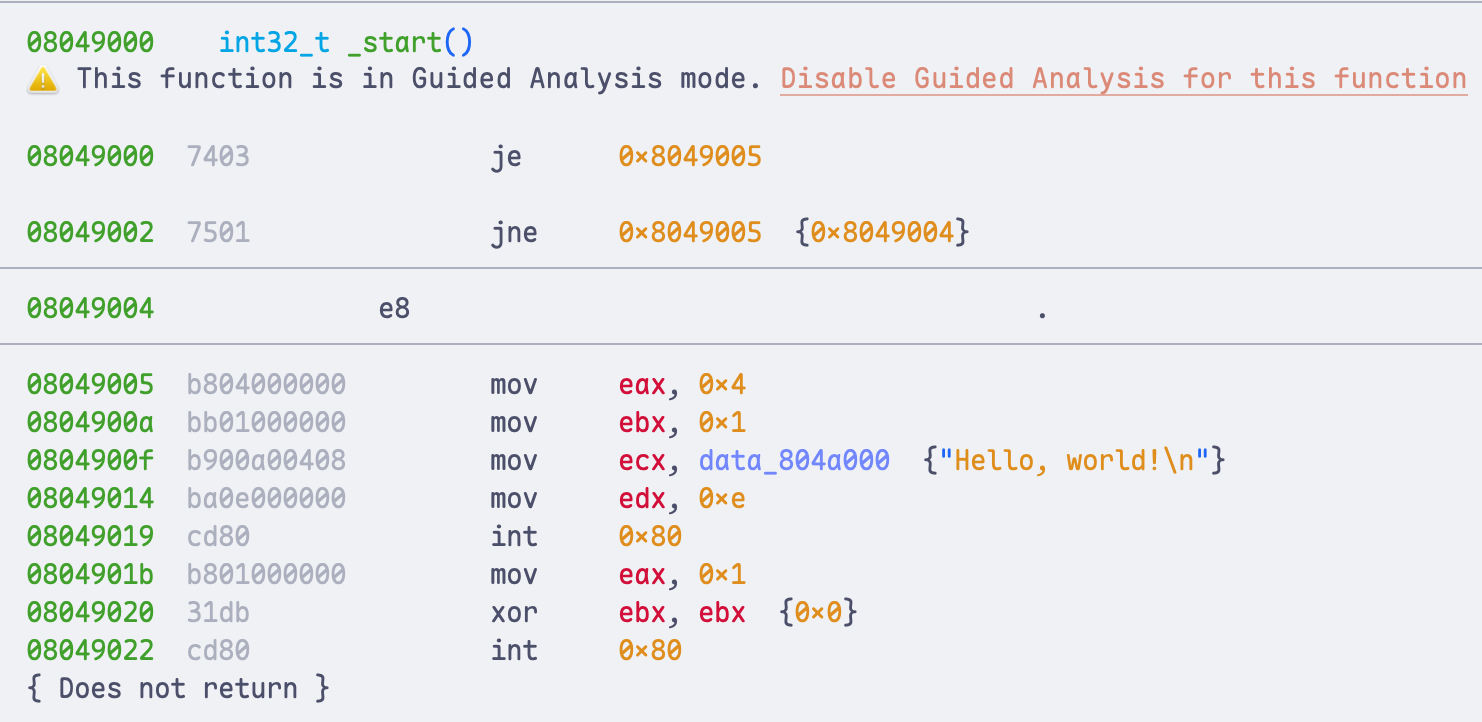

Let’s look at a piece of assembly code and then compare the disassembly result. The following program is a simple “Hello world” program:

; nasm -f elf32 -o hello.o hello.asm

; ld -m elf_i386 -o hello hello.o

; strip hello

global _start

section .data

msg: db "Hello, world!", 10

len: equ $ - msg

section .text

_start:

; --- Anti-disassembly trick start ---

jz real_code

jnz real_code

db 0xE8 ; fake byte

real_code:

; Linux write(1, msg, len)

mov eax, 4

mov ebx, 1

mov ecx, msg

mov edx, len

int 0x80

; exit(0)

mov eax, 1

xor ebx, ebx

int 0x80Note that at the _start label, both jz and jnz jump to the same target, and they are immediately followed by db 0xE8. This inserts a junk byte into the program. We will explain in detail how this works in a moment; for now, let’s first look at the disassembly of the stripped binary produced by objdump:

> objdump -d -M intel hello

hello: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08049000 <.text>:

8049000: 74 03 je 0x8049005

8049002: 75 01 jne 0x8049005

8049004: e8 b8 04 00 00 call 0x80494c1

8049009: 00 bb 01 00 00 00 add BYTE PTR [ebx+0x1],bh

804900f: b9 00 a0 04 08 mov ecx,0x804a000

8049014: ba 0e 00 00 00 mov edx,0xe

8049019: cd 80 int 0x80

804901b: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

8049020: 31 db xor ebx,ebx

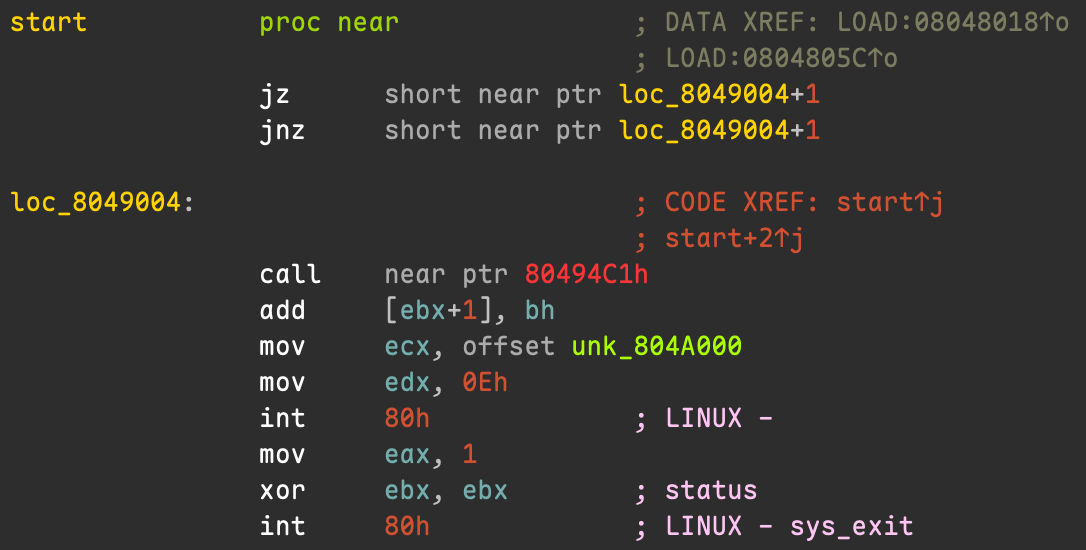

8049022: cd 80 int 0x80We can see that the junk byte 0xE8 following je and jne is interpreted as part of an instruction and, together with subsequent bytes, is disassembled as call 0x80494c1. If we switch to IDA, we can observe that it is likewise successfully confused by this trick.

This means that both the linear sweep disassembler objdump and the recursive descent disassembler IDA are susceptible to this obfuscation.

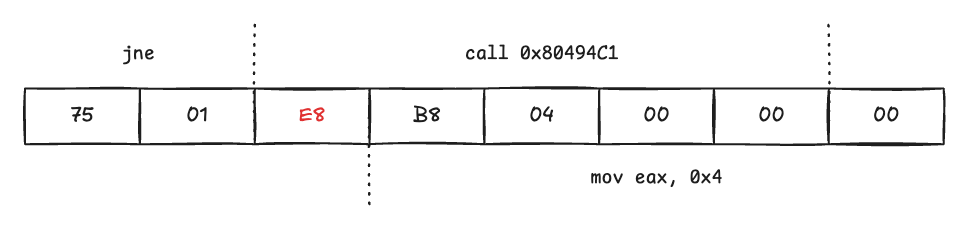

The underlying principle here is what we discussed earlier: disassemblers tend to trust the false branch first. As a result, they start disassembling from the byte immediately following jnz, so the malicious byte 0xE8 that we inserted is treated as code and decoded as part of an instruction. Conceptually, the situation looks roughly like this:

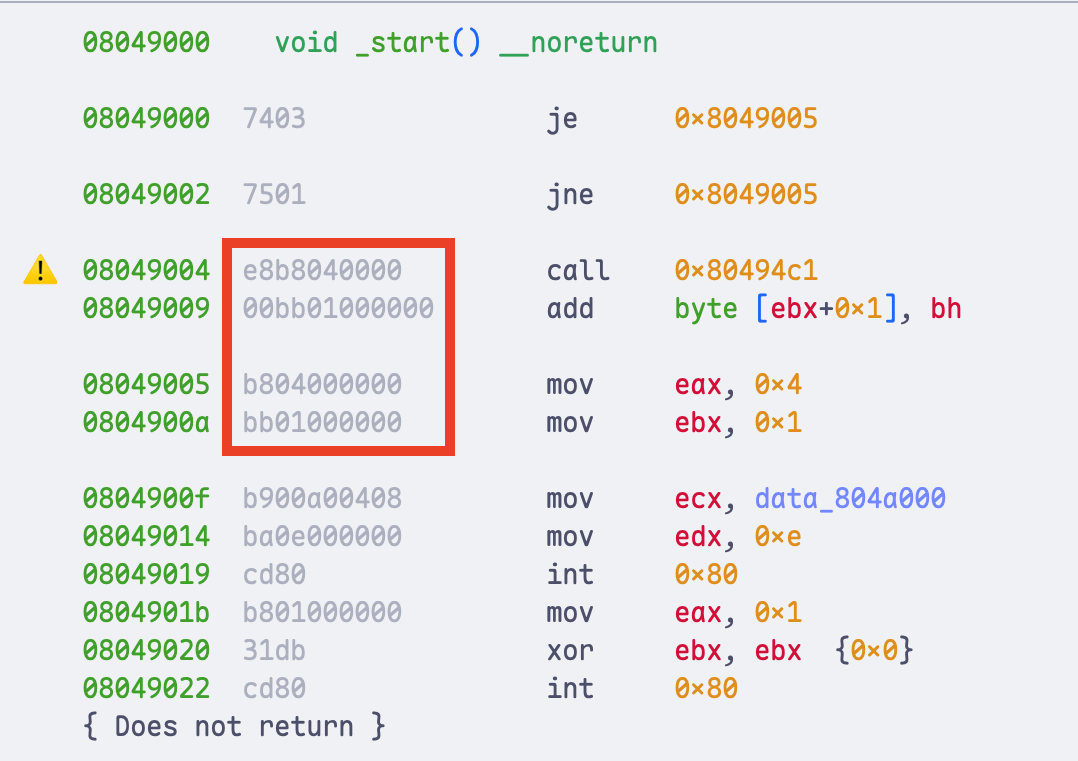

Here I would like to praise Binary Ninja. Although it can also be confused by this trick, it still manages to correctly disassemble the code that follows. After a closer look, we can see that even though it has already used the bytes B8 04 00 00 00 BB 01 00 00 00 to produce two incorrect instructions, it still marks the potentially incorrect region and reuses those bytes to correctly disassemble the subsequent code, as shown in the figure.

So how should a reverse engineer restore this code fragment during analysis? The answer is that we can mark 0xE8 as data. Once we do this, the disassembler can correctly decode the instructions that follow. In IDA, we can first press D on the entire opcode E8 B8 04 00 00 of call 0x80494c1 to convert it to data, then press C on B8 to convert B8 04 00 00 back to code. In this way, E8 is transformed back into data and will no longer be interpreted as an instruction byte.

In Binary Ninja, we can use its Guided Analysis feature. The official documentation describes it as follows:

Guided Analysis provides granular control over which basic blocks are included or excluded from analysis. It is especially useful for analyzing obfuscated code, troubleshooting analysis issues, or focusing on specific execution paths while excluding irrelevant code.

Guided Analysis 提供對哪些基本塊被包含或排除在分析之外的粒度控制。對於分析被混淆的程式碼、排除分析問題、或在排除不相關的程式碼的同時聚焦於特定執行路徑特別有用。

Concretely, to use this feature, we can right-click at the instruction jne 0x8049005 and select “Halt Disassembly” to isolate the corresponding byte. The result is shown below:

We can see that the e8 byte in the figure has been successfully isolated, and the subsequent disassembly is now all correct.

(Note: During discussions with the Binary Ninja developers, I also learned that there is a dedicated plugin for this purpose. I have not used it yet myself, but it looks very cool!)

A Jump Instruction with a Constant Condition (Opaque Predicate)

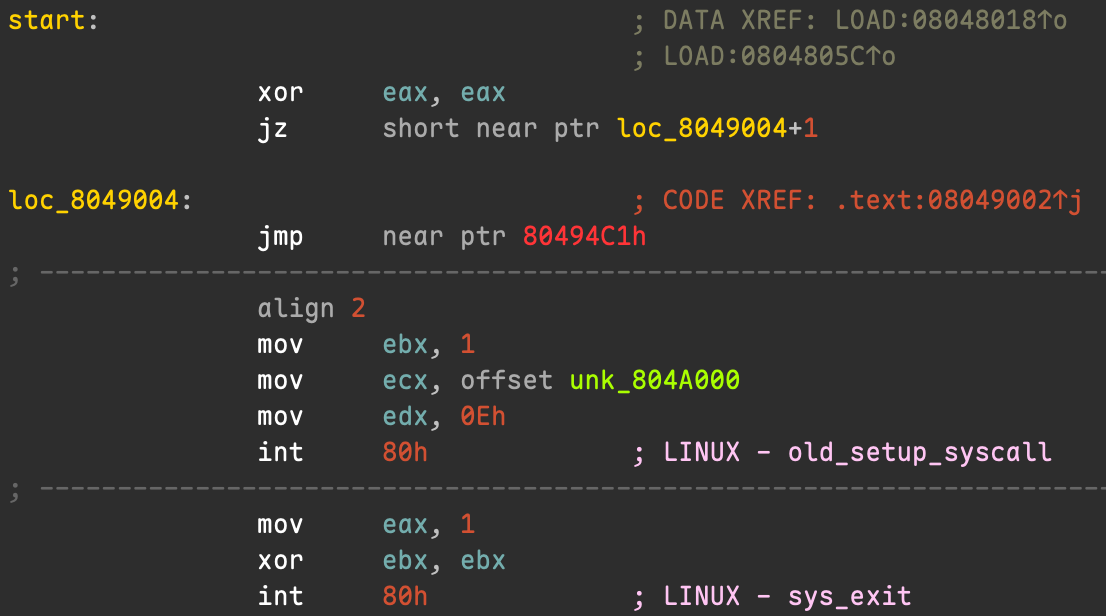

The second trick we will introduce is very similar to the previous one. Again, let’s start from the code:

; nasm -f elf32 -o hello.o hello.asm

; ld -m elf_i386 -o hello hello.o

; strip hello

global _start

section .data

msg: db "Hello, world!", 10

len: equ $ - msg

section .text

_start:

; --- Anti-disassembly trick start ---

xor eax, eax

jz real_code

db 0xE9 ; fake byte

real_code:

; Linux write(1, msg, len)

mov eax, 4

mov ebx, 1

mov ecx, msg

mov edx, len

int 0x80

; exit(0)

mov eax, 1

xor ebx, ebx

int 0x80The main difference from the first example is that here we use xor eax, eax before jumping to real_code with jz; the rest is essentially the same. Now let’s inspect how objdump and IDA are confused by this:

> objdump -d -M intel hello

hello: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08049000 <.text>:

8049000: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

8049002: 74 01 je 0x8049005

8049004: e9 b8 04 00 00 jmp 0x80494c1

8049009: 00 bb 01 00 00 00 add BYTE PTR [ebx+0x1],bh

804900f: b9 00 a0 04 08 mov ecx,0x804a000

8049014: ba 0e 00 00 00 mov edx,0xe

8049019: cd 80 int 0x80

804901b: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

8049020: 31 db xor ebx,ebx

8049022: cd 80 int 0x80The principle here is to use xor eax, eax to force the zero flag (ZF) to 1. Under this condition, jz becomes an unconditional jump rather than a conditional one. When the disassembler encounters jz, it does not know that this is effectively an unconditional jump, so it still prioritizes the false branch—the byte immediately following jz. Since that byte is the malicious data 0xE9, the disassembler ends up decoding E9 B8 04 00 00 as jmp 0x80494c1.

The method of restoring the true control flow during analysis is similar to the previous example: simply mark the junk data byte as data.

Impossible Disassembly

The two anti-disassembly tricks we discussed above both rely on inserting a malicious data byte after a conditional jump to corrupt the disassembly starting at that byte, thereby preventing the correct instructions that follow from being properly recognized. This works because the inserted byte happens to be the opcode of some multi-byte instruction. We call such a byte a rogue byte, because it is not actually part of the real code—it is just a data byte, so at runtime these rogue bytes can all be ignored.

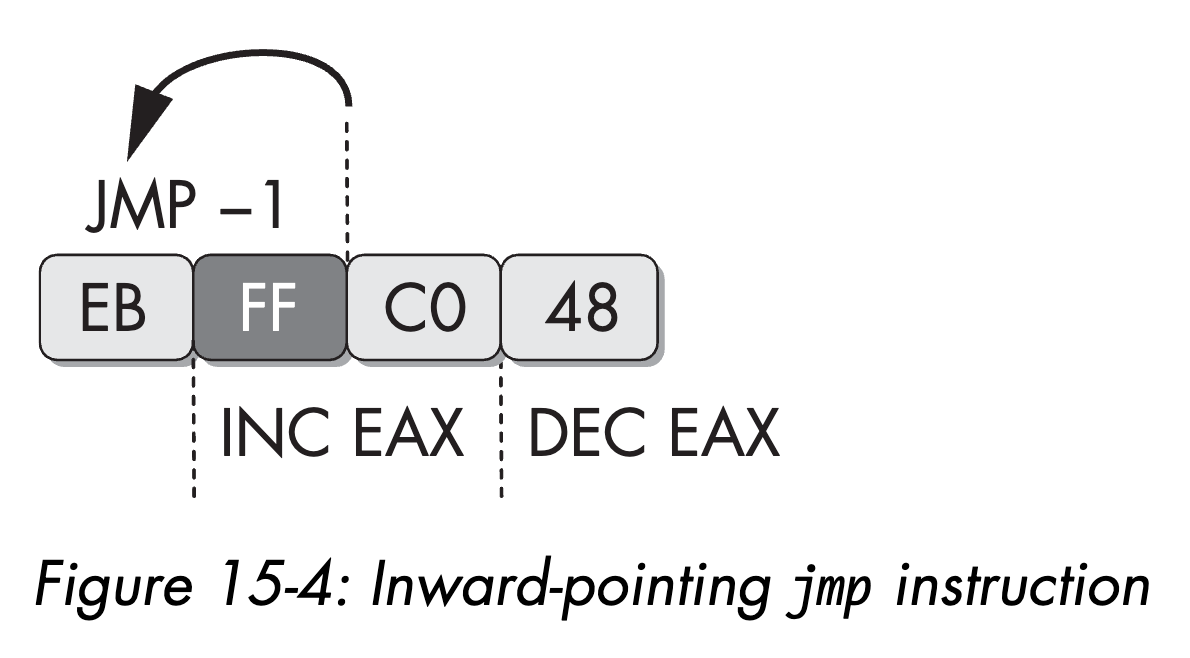

But what if this rogue byte cannot be ignored? What if it is also part of a legitimate instruction that will actually execute? This brings us to the next technique: impossible disassembly. With this technique, the same byte may simultaneously belong to multiple instructions that will all be executed.

The figure below is taken from the chapter on this technique in Practical Malware Analysis: The Hands-On Guide to Dissecting Malicious Software (a highly recommended read). In this example, within a 4-byte sequence, the first instruction is a 2-byte jmp. The target address of this jump happens to land on the second byte of that instruction. This causes no problem, because the byte FF is also the first byte of the next 2-byte instruction (inc eax).

As a result, this sequence effectively jumps backwards, increments eax, then decrements eax, which is equivalent to a multi-byte nop that can be inserted anywhere in the code to confuse disassemblers. Let’s look at some assembly code:

; nasm -f elf32 -o hello.o hello.asm

; ld -m elf_i386 -o hello hello.o

; strip hello

section .data

msg: db "Hello, world!", 10

msg_len equ $ - msg

global _start

section .text

_start:

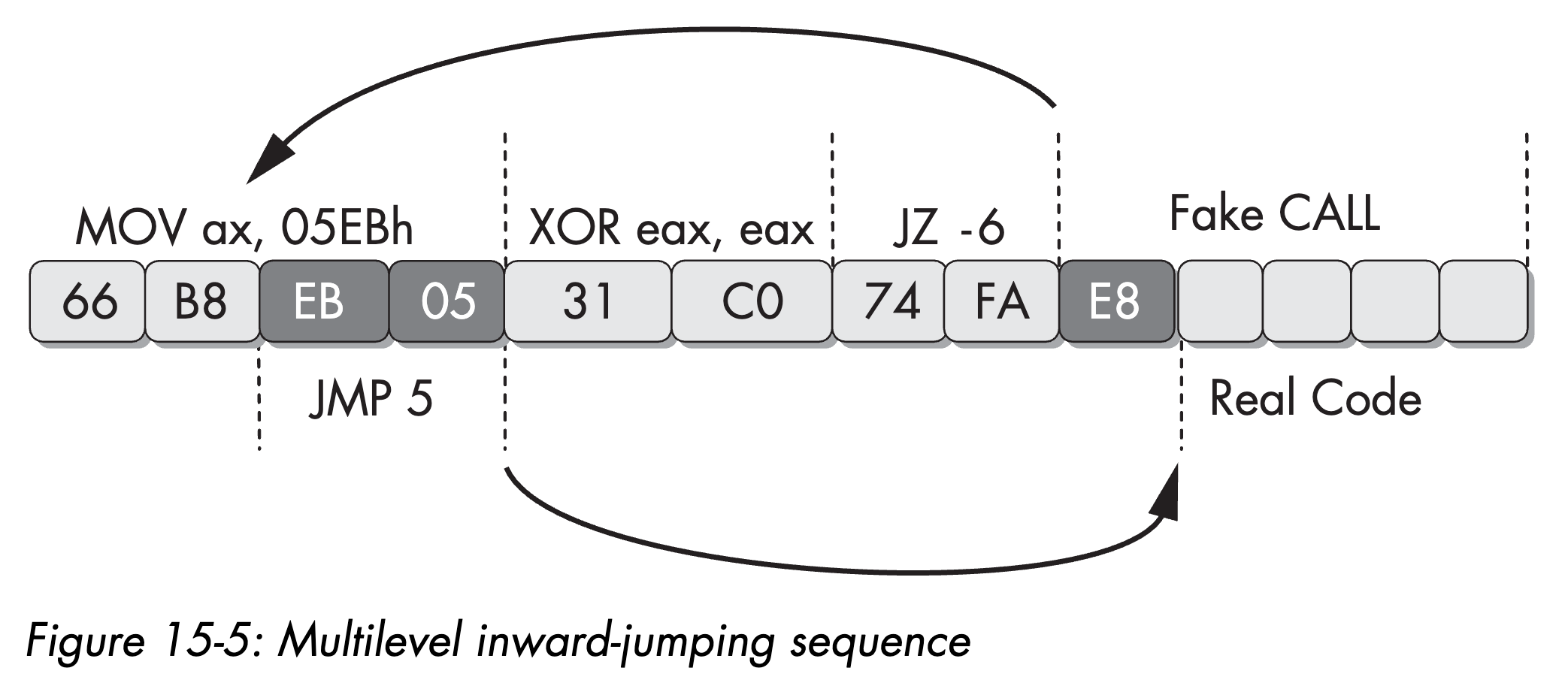

db 0x66, 0xB8, 0xEB, 0x05, 0x31, 0xC0, 0x74, 0xFA, 0xE8

real_code:

mov eax, 4 ; sys_write

mov ebx, 1 ; stdout

mov ecx, msg

mov edx, msg_len

int 0x80

; exit

mov eax, 1

xor ebx, ebx

int 0x80At the very beginning of this program, we place the bytes 0x66, 0xB8, 0xEB, 0x05, 0x31, 0xC0, 0x74, 0xFA, 0xE8 into memory. The disassembly of this sequence is shown in the following figure, again taken from the book:

We can see that this code loads 0x5EB into the ax register and then clears eax, which sets ZF = 1. Therefore, the subsequent jz will always branch, so the control flow first jumps back 6 bytes and then jumps forward 5 bytes into the “real code” region. From the disassembler’s perspective, however, 74 FA is interpreted as jz -6, a conditional jump. Consequently, the disassembler processes the false branch first, which leads it to interpret the adjacent E8 as part of a bogus call instruction.

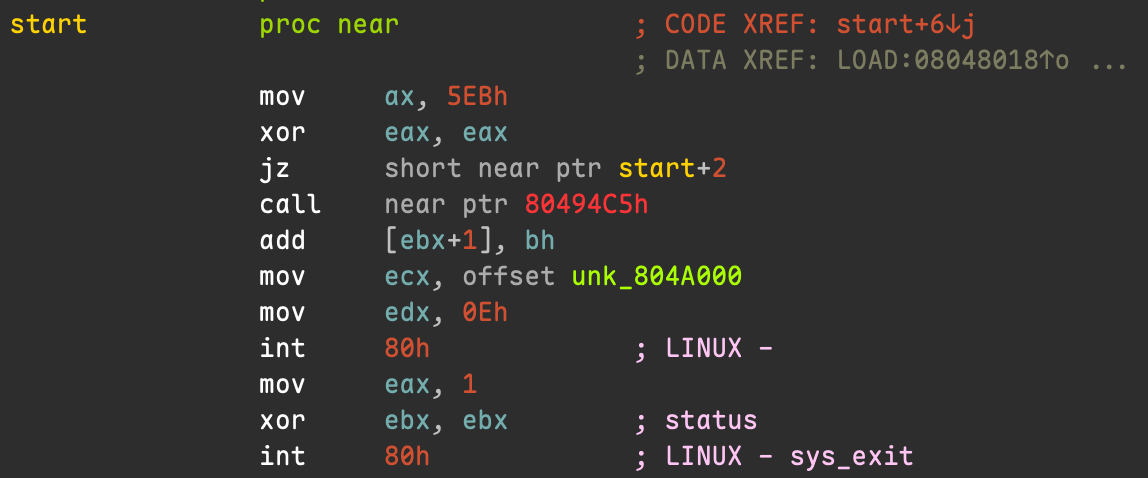

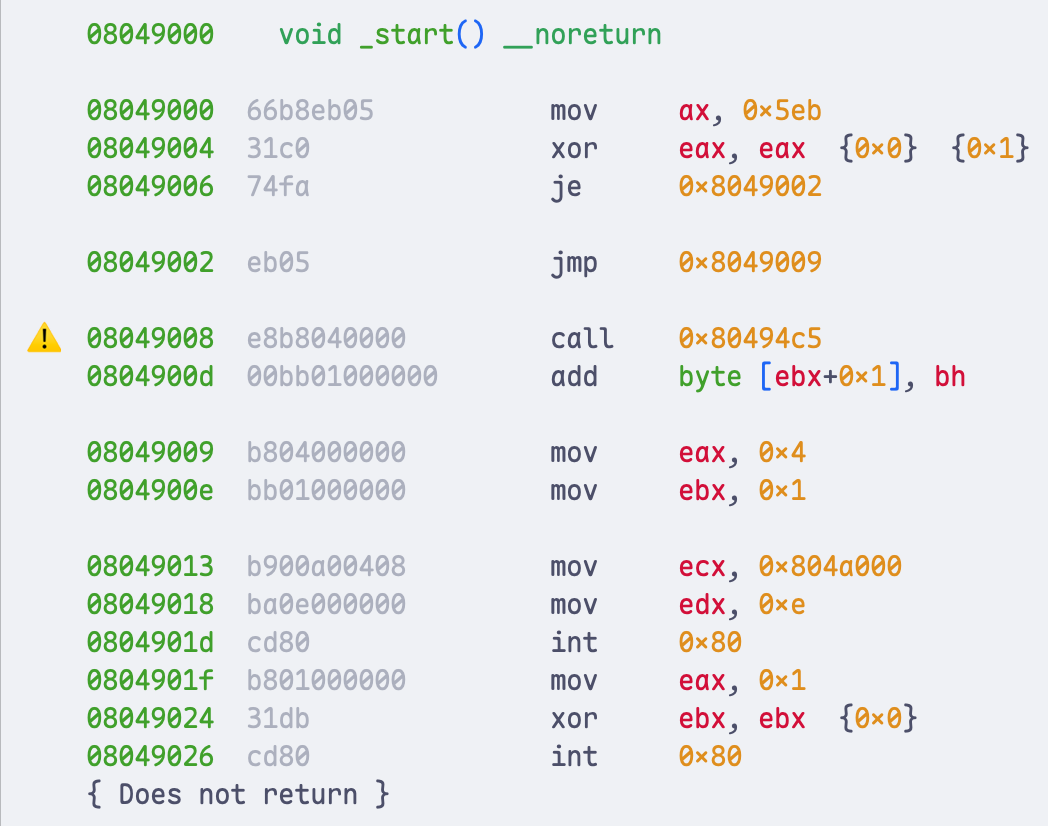

Now let’s assemble this code and look at IDA’s disassembly:

As we can see, IDA indeed interprets this as a fake call. Binary Ninja, on the other hand, once again manages to correctly disassemble the subsequent code:

The book notes that:

“No disassembler currently on the market will represent a single byte as being part of two instructions.”

However, it now appears that Binary Ninja has successfully achieved this, and does so very elegantly. My deepest respect to the Binary Ninja development team.

Once we understand this concept, we can wrap this sequence into a C macro and reuse it throughout our code to increase the complexity of analyzing the entire program:

#include <stdio.h>

#define IMPOSSIBLE_DISASM() \

__asm__ __volatile__( \

".byte 0x66, 0xB8, 0xEB, 0x05, 0x31, 0xC0, 0x74, 0xFA, 0xE8");

int main()

{

IMPOSSIBLE_DISASM();

printf("Hello, world\n");

}Of course, other languages such as Go and Rust can adopt similar tricks to achieve anti-disassembly effects. Here is an example using an inline function in Zig:

const std = @import("std");

inline fn impossible_disasm() void {

asm volatile (

\\ .byte 0x66, 0xB8, 0xEB, 0x05, 0x31, 0xC0, 0x74, 0xFA, 0xE8

);

}

pub fn main() !void {

impossible_disasm();

std.debug.print("Hello, world\n", .{});

}So how should a reverse engineer repair such a binary? For IDA users, one option is to use IDAPython or IDC to call the PatchByte function and replace 66 B8 EB 05 and 74 FA E8 with NOP instructions, thereby restoring a normal control flow. For example, we can write a function to help us do this:

def NopBytes(start, length):

for i in range(0, length):

PatchByte(start + i, 0x90) # 0x90 for NOP

MakeCode(start)Binary Ninja users can use the GUI to select the instructions to be converted into NOPs, right-click, choose Patch, and then select “Convert to NOP.” Alternatively, this can also be done via the Binary Ninja Python API, as shown below:

def nop_bytes(start, length):

for i in range(length):

bv.write(start + i, b"\x90")

bv.update_analysis_and_wait()Conclusion

For me, delving into anti-disassembly techniques has been a very enjoyable experience. Along the way, I gained a much deeper understanding of how disassemblers work and how to design potential obfuscation strategies that target their algorithms. Although I do not believe these techniques can stop any truly capable reverse engineer from understanding a program, they can at least slow them down.

At the same time, these tricks are also well-suited for CTF challenges and are very helpful for learning assembly language.

You can find more anti-disassembly techniques here: https://unprotect.it/category/anti-disassembly/

References

- Practical Malware Analysis: The Hands-On Guide to Dissecting Malicious Software

- Anti-disassembly with a rogue byte | Gelven’s Blog

- ANTI-DISASSEMBLY TECHNIQUES | Medium

- Malware Dev – Chapter 07 – Anti-Disassembly Strategies – { Eric’s Blog }

The Binary Ninja version used in this article is 5.2.8614-Stable; the IDA Free version is 9.0.241217 for macOS. ↩︎